What is a Check Valve and How it Works

Check valves are found in almost every industrial application acting as non-return or one-way valves. Generally simple devices, check valves perform a vital function preventing reverse flows, damage and ensuring efficient operations. Reverse flow can, for example, result in water hammer. This phenomenon can see repeated extreme pressure surges in connected pipework, valves and pumps that may fatally damage or rupture the system and its pipework. Even if a failure does not occur immediately the repeated impact of water hammer can promote fatigue that may also ultimately result in a loss of system integrity.

Featuring a single inlet and outlet, check valves are operated by a pressure differential. Above a certain upstream pressure, the valve will automatically open without requiring any other intervention. Known as the cracking pressure, this minimum operational pressure is one of the key characteristics specified in all check valves. Chemicals, pulp and paper, food processing, water and wastewater treatment, industrial, marine and mining, pumps, pipelines, power generation and HVAC are among the many fluid flow and pumping applications that feature check valves.

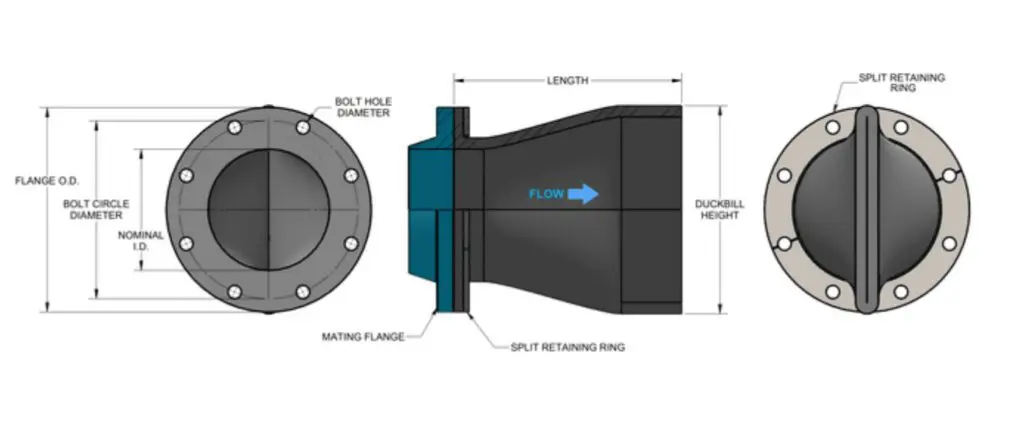

Frequently check valves are placed in series, for instance in water systems to prevent backflow of contaminated water into clean water supply lines. With a huge range of potential applications, there are also multiple types of check valve which use many different materials such as metal, polymers and rubber. Common designs include swing or flap check valves in which a metal disc pivots on a hinge or trunnion to prevent reverse flow. Larger check valves are typically of the swing or flap type. As the name suggests, ball and spring ball check valves feature a ball that mounts in an appropriately profiled seat. Duck bill check valves rely on a flexible rubber diaphragm which creates a valve that is normally closed unless positive pressure is applied.

However, unlike their metal swing or flap check valve counterparts rubber duckbill check valves cannot rust, seize, or bind, typically increasing reliability and longevity. Similarly, rubber check valves do not suffer from mechanical wear, a factor which can negatively influence check valves manufactured from other materials.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT CHECK VALVE

When specifying check valves, many factors must be considered to ensure the correct choice. For example, it is important to ensure that any check valve is manufactured from suitable materials that are compatible with the liquid or gas that will be used, for example using a rubber duckbill check valve where they are appropriate. Valve rating, line size, type of installation such as horizontal or vertical, dimensions and connection type, maximum leakage rate, pressure drop, and any special requirements should all for part of an in-depth evaluation. It is also important to ensure that the correct type of valve is used in each application.

However, while for most types of valve the fully open gate does not significantly restrict the flow, in a check valve the degree of opening is dependent on the differential pressure. Nonetheless, check valves are frequently specified like other kinds of valve and based on the largest valve flow coefficient (Cv) possible, rather than actual operating conditions. As a result, the valve may only partially open where the flow rate is less than required. Partially opened valves may see increased resistance and pressure drop, as well as phenomena such as valve flutter. Excessive flutter results in wear which inevitably increases the possibility of component failure. In the case of check valves, this can allow reverse flow and all the associated problems that may arise under those conditions.

In check valve applications, for example, higher Cv values may be detrimental given this increases the likelihood of a partially open valve. A high Cv valve in a low flow application is likely to increase the potential for wear on the valve components and a higher pressure drop than predicted, given that pressure drop is normally calculated on the basis of a valve being fully open.

The correct sizing of a check valve is therefore a critical consideration that is often misunderstood. In applications where there is insufficient flow to keep the valve against its stop a lower Cv value valve is required to prevent characteristics like flutter. Sizing check valves should thus be based on the specific application, rather than the line size, to ensure the valve is fully open or closed under typical operating conditions. This characteristic of check valves is often overlooked, and it is commonly found that such problems ultimately arise from poorly specified check valves, rather than the actual valves themselves.

WHEN TO REPLACE CHECK VALVES

With the potentially significant negative outcomes that can result in response to a failed check valve, ensuring check valves are well maintained and operate correctly is critical for plant operators. For example, check valves are used in all stormwater and wastewater systems where they prevent backflow. Failed check valves which are corroded or jammed can result in standing water or flooding and associated health impacts because of contact with contaminated water. Check valve failure modes associated with wear or poor maintenance can include problems related to noise and vibration from water hammer, reverse flow, leakage or damage. Sticking valves can occur when material like scale or debris is trapped between the valve body and the moving parts such as the disc or ball. Where the valve seat or other elements become damaged or material is lodged this can result in leaking. Along with contamination, other factors which may negatively affect check valves include high temperatures, worn elastomers and seat seals, incorrect installation or poor maintenance and assembly. Valves may also stick or leak as they age and begin to break down.

As mechanical check valves deteriorate, they typically give warning signs of their poor condition. For example, they may start to vibrate, emit noises or chatter and it is also possible that components may fail and be lost from the mechanism. As check valves fail reverse flows may also occur. Simply listening for fluid flow when the valve is in the closed position is indicative of leakage and a strong warning sign to act. It is useful to note that Rubber Duckbill Check Valves are “passive” devices and not prone to this type of deterioration. Relatively simply measures such as minimizing debris in the line through filters and correctly lubricating check valve components can help to eliminate premature failure. However, it is also worth noting that check valves do need to be replaced on a regular basis. Products that are based on high quality and experienced engineering inevitably has a significant impact on performance with cheaper products often a false economy. While typical component lifespans are application specific, manufacturers suggest metal and plastic check valves should be replace every 5-7 years whereas check valves manufactured from rubber may remain fully serviceable for up to 35-50 years.

Check valves are typically a low-cost component and as such are frequently overlooked. This can be a high-risk approach given that the cost of check valve failure is significant. The potential for catastrophe is real where reverse flow can halt production or even extensively damage a facility. Consequently, where check valves begin to show any sign of trouble plant operators must promptly renew the component with a high-quality replacement.

SOURCE: https://www.procoproducts.com/what-is-a-check-valve-how-it-works/